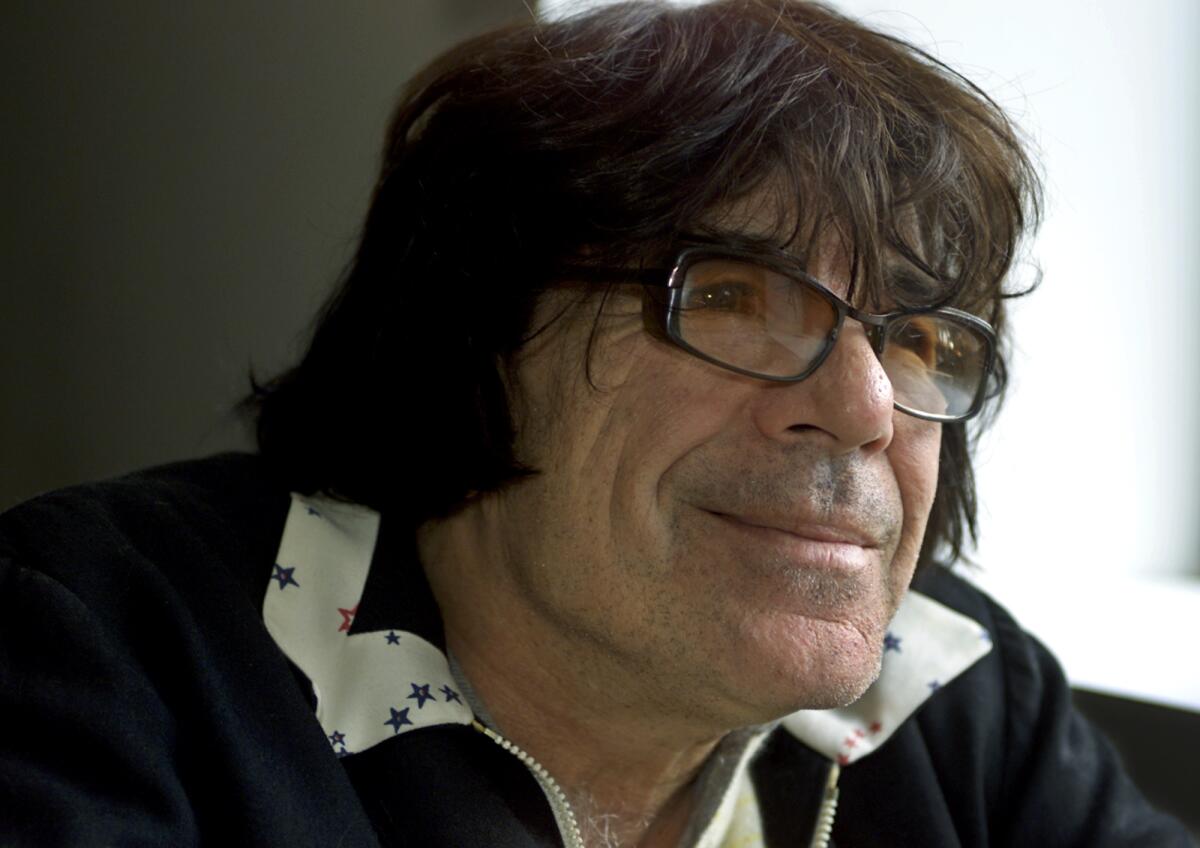

Chuck E. Weiss, musician and raconteur of ‘Chuck E.’s in Love’ fame, dies at 76

Chuck E. Weiss, the singer, songwriter, Tom Waits collaborator, L.A. club owner, raconteur and subject of Rickie Lee Jones’ hit “Chuck E.’s in Love,” has died. Weiss was a fixture in Hollywood for nearly 50 years, including hosting an 11-year Monday night residency at the Central on the Sunset Strip. He went on to become the Central’s co-owner, with Johnny Depp and others, when the club changed its name to the Viper Room.

Weiss died at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in L.A. on July 20. He was 76. His death was confirmed by his friend of more than 50 years, Chuck Morris, who cited cancer as the cause.

Weiss first earned fame not for his music but as the “Chuck” of Jones’ jazz-inspired 1979 hit. In it, she notes her protagonist’s newly mysterious behavior: “He sure has acquired this kinda cool / And inspired sorta jazz when he walks / Where’s his jacket and his old blue jeans? / Well, this ain’t healthy, it is some kinda clean.”

The reason for this transformation arrives in the song’s title and refrain. The complication comes near the coda: “Chuck E.’s in love with the little girl singing this song.”

Hollywood musical fixture Chuck E. Weiss died on July 19, at age 76. Here, one-time running mate Rickie Lee Jones pays tribute to Weiss’ cool charisma.

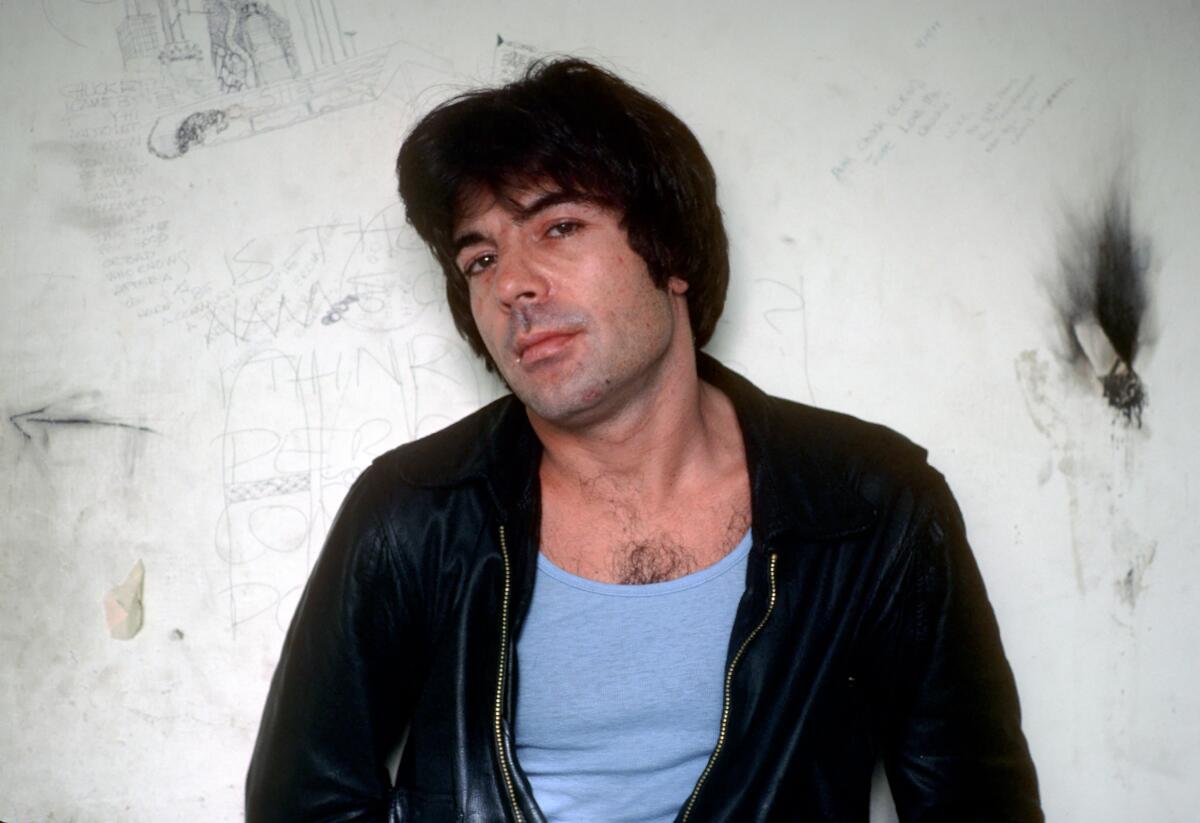

Whether accurate or poetic license, “Chuck E.’s in Love” was Jones’ breakthrough and cemented Weiss’ legend in the American pop imagination. By the time the song started creeping up the charts, Weiss was already a looming presence on the club circuit: The Times described him as “one of L.A.’s perennial hangers-out” in a 1979 profile.

Born into music as the son of a Denver record store owner, Charles Edward Weiss first met Waits in Denver, where Weiss was playing drums with touring blues artists including Muddy Waters and Lightnin’ Hopkins. Weiss had been at a Waits gig and approached the singer after the set. “I was wearing some platform shoes and a chinchilla coat, and I was slipping on the ice on the street outside because I was so high,” Weiss recalled in a 1999 interview, adding that he invited Waits to record with him at a local studio. “He looked at me like I was from outer space, man. Next night I saw him at the coffee shop next door. We started hanging out together. We’ve been friends ever since.”

Weiss co-wrote “Spare Parts (A Nocturnal Emission),” a noir-ish song on Waits’ 1975 barfly masterpiece, “Nighthawks at the Diner.” The song captures the essence of lowlife L.A. in which Weiss moved, one where “bums showed up just like bounced checks / Rubbin’ their necks / And the sky turned the color of Pepto-Bismol / And my old sports coat full of promissory notes.”

Fueled by a pharmacy’s worth of drugs and a renegade spirit, Weiss led an artistic existence that echoed those described in the beatnik work of Jack Kerouac and the gritty stories of Raymond Chandler and Charles Bukowski. In 1975, he moved into the famed West Hollywood rock ‘n’ roll motel the Tropicana because, he told one interviewer, “I was driving to and from Silver Lake to [Duke’s Coffee Shop] everyday to eat.” In doing so, he joined a rockstar-heavy spot that at one time or another housed Waits, Bob Marley, Jim Morrison, Warren Zevon, the Ramones, Iggy Pop and Blondie.

Weiss knew the young singer Jones from nights at the Troubadour, where he had worked (before getting fired within a month), and after she and Waits developed a relationship, the trio became a constant presence on the music scene. They were described in The Times as “three Runyonesque characters [who] were as much a part of the west Hollywood hotel Tropicana’s fauna as the mastodons that stocked the La Brea tar pits way back when.”

The darker side of that existence was largely hidden from the media. Both Jones and Weiss had become addicted to heroin as “Chuck E.’s in Love” and her Grammy-winning self-titled debut album were making them famous. The situation prompted Waits to move east, he told BAM in 1982: “There was always the danger of getting sucked down,” Waits said, adding that by the end of 1979, “I felt I’d painted myself into a corner. I’d fallen in with a bad crowd and needed a new landscape, a new story.”

Despite Weiss’ addiction, “Chuck E.’s in Love” opened doors. “This song has brought people out of the woodwork,” Weiss told The Times in ‘79, adding that he’d been getting label offers. He described his style as “sort of like a bohemian street rockabilly kind of thing, a little rhythm and blues.” His album of demos, “The Other Side of Town,” was released in 1981. It featured appearances by Jones on one song, “Sidekick,” as well as by Mac “Dr. John” Rebennack (who was Jones’ beau at the time).

Weiss was a regular on the Sunset Strip across the 1980s. Though he was hardly the best singer — he was once compared to “that guy in the audience who always seems to get the microphone stuck in his face come sing-along time” — he and his blues-rock band the Goddamn Liars held court at the Central on a weekly basis.

The club, which was a gangster hangout when it was called the Melody Room, went up for sale in the early 1990s, and Weiss, his friend Depp and a few other investors renamed it the Viper Room. When it opened in 1993, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers christened the stage and Depp’s fame gave it instant buzz. That changed less than a year later, when actor River Phoenix collapsed in front of the club after overdosing and died.

The media attention prompted Weiss to shutter the place for a week out of respect for Phoenix’s memory. When it opened the following Monday, Weiss and his Liars dedicated the set to the actor. In the mid-1990s, Weiss moved his residency to North Hollywood and renamed it Hot House.

By then, Weiss, long known as an inexhaustible party dude, had gotten sober, says his friend Morris, and “after years of drug abuse he became a leader of turning people around from the problems of drug and alcohol excess.” Added Morris, “His speeches at AA meetings in Los Angeles were legendary.”

Weiss recorded his first official solo album in 1998. Called “Extremely Cool,” it was co-produced by the husband/wife collaborating team of Waits and Kathleen Brennan. In an interview after its release, Weiss praised his longtime friend Waits: “He was really a mentor, telling me what I needed to do to get it done. It’s kinda like Snoop and Dr. Dre!”

The musician teamed up with Waits again in 2014 for “Red Beans and Weiss,” which was co-produced by Depp. Also steeped in the blues, the album found Weiss growling his way through songs about bombing train tracks during a war, brewing music he calls “the knucklehead stuff,” a lady named Shushie and another one named Boston Blackie. It was hardly a smash hit, but that never seemed to bother Weiss.

“I’m not known well enough to have any conceptions at all yet,” Weiss told an interviewer in 1999, of his musical approach. “I guess everybody has a different idea of what it is that I’m doing. I’d just like to say that I don’t like to be labeled. That’s a big asset.”

A regular at Canter’s Deli in the Fairfax District, in recent years he’d meet up with friends there for lunch. After his death, singer and songwriter Kinky Friedman’s Facebook page offered a salute, via a spokesperson: “Kinky rarely made a trip to L.A. without meeting Chuck E. for lunch at Canter’s Deli.” The note added that Friedman and Weiss had “just recently finished writing a song together titled, appropriately enough, ‘See You Down the Highway.’”

Weiss never married and didn’t have any children. He is survived by his older brother, Byron “Whiz” Weiss.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.